Hand-written Digit Recognition¶

In this tutorial, we’ll give you a step-by-step walkthrough of building a hand-written digit classifier using the MNIST dataset.

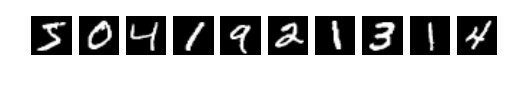

MNIST is a widely used dataset for the hand-written digit classification task. It consists of 70,000 labeled grayscale images of hand-written digits, each 28x28 pixels in size. The dataset is split into 60,000 training images and 10,000 test images. There are 10 classes (one for each of the 10 digits). The task at hand is to train a model that can correctly classify the images into the digits they represent. The 60,000 training images are used to fit the model, and its performance in terms of classification accuracy is subsequently validated on the 10,000 test images.

Figure 1: Sample images from the MNIST dataset.

This tutorial uses MXNet’s high-level Gluon interface to implement neural networks in an imperative fashion. It is based on the corresponding tutorial written with the symbolic approach.

Prerequisites¶

To complete this tutorial, you need:

- MXNet. See the instructions for your operating system in Setup and Installation.

- The Python

requestslibrary. - (Optional) The Jupyter Notebook software for interactively running the provided

.ipynbfile.

$ pip install requests jupyter

Loading Data¶

The following code downloads the MNIST dataset to the default location (.mxnet/datasets/mnist/ in your home directory) and creates Dataset objects train_data and val_data for training and validation, respectively.

These objects can later be used to get one image or a batch of images at a time, together with their corresponding labels.

We also immediately apply the transform_first() method and supply a function that moves the channel axis of the images to the beginning ((28, 28, 1) -> (1, 28, 28)), casts them to float32 and rescales them from [0, 255] to [0, 1].

The name transform_first reflects the fact that these datasets contain images and labels, and that the transform should only be applied to the first of each (image, label) pair.

import mxnet as mx

# Select a fixed random seed for reproducibility

mx.random.seed(42)

def data_xform(data):

"""Move channel axis to the beginning, cast to float32, and normalize to [0, 1]."""

return nd.moveaxis(data, 2, 0).astype('float32') / 255

train_data = mx.gluon.data.vision.MNIST(train=True).transform_first(data_xform)

val_data = mx.gluon.data.vision.MNIST(train=False).transform_first(data_xform)

Since the MNIST dataset is relatively small, the MNIST class loads it into memory all at once, but for larger datasets like ImageNet, this would no longer be possible.

The Gluon Dataset class from which MNIST derives supports both cases.

In general, Dataset and DataLoader (which we will encounter next) are the machinery in MXNet that provides a stream of input data to be consumed by a training algorithm, typically in batches of multiple data entities at once for better efficiency.

In this tutorial, we will configure the data loader to feed examples in batches of 100.

An image batch is commonly represented as a 4-D array with shape (batch_size, num_channels, height, width).

This convention is denoted by “NCHW”, and it is the default in MXNet.

For the MNIST dataset, each image has a size of 28x28 pixels and one color channel (grayscale), hence the shape of an input batch will be (batch_size, 1, 28, 28).

Another important consideration is the order of input samples.

When feeding training examples, it is critical not feed samples with the same label in succession since doing so can slow down training progress.

Data iterators, i.e., instances of DataLoader, take care of this issue by randomly shuffling the inputs.

Note that we only need to shuffle the training data – for validation data, the order does not matter.

The following code initializes the data iterators for the MNIST dataset.

batch_size = 100

train_loader = mx.gluon.data.DataLoader(train_data, shuffle=True, batch_size=batch_size)

val_loader = mx.gluon.data.DataLoader(val_data, shuffle=False, batch_size=batch_size)

Approaches¶

We will cover two approaches for performing the hand-written digit recognition task. In our first attempt, we will make use of a traditional neural network architecture called Multilayer Perceptron (MLP). Although this architecture lets us achieve over 95 % accuracy on the validation set, we will recognize and discuss some of its drawbacks and use them as a motivation for using a different network. In the subsequent second attempt, we introduce the more advanced and very widely used Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architecture that has proven to work very well for image classification tasks.

As a first step, we run some convenience imports of frequently used modules.

from __future__ import print_function # only relevant for Python 2

import mxnet as mx

from mxnet import nd, gluon, autograd

from mxnet.gluon import nn

Defining a network: Multilayer Perceptron (MLP)¶

MLPs consist of several fully connected layers. In a fully connected (short: FC) layer, each neuron is connected to every neuron in its preceding layer. From a linear algebra perspective, an FC layer applies an affine transform Y = X W + b to an input matrix X of size (n x m) and outputs a matrix Y of size (n x k). The number k, also referred to as hidden size, corresponds to the number of neurons in the FC layer. An FC layer has two learnable parameters: the (m x k) weight matrix W and the (1 x k) bias vector b.

In an MLP, the outputs of FC layers are typically fed into an activation function that applies an elementwise nonlinearity. This step is crucial since it gives neural networks the ability to classify inputs that are not linearly separable. Common choices for activation functions are sigmoid, hyperbolic tangent (“tanh”), and rectified linear unit (ReLU). In this example, we’ll use the ReLU activation function since it has several nice properties that make it a good default choice.

The following code snippet declares three fully connected (or dense) layers with 128, 64 and 10 neurons each, where the last number of neurons matches the number of output classes in our dataset.

Note that the last layer uses no activation function since the softmax activation will be implicitly applied by the loss function later on.

To build the neural network, we use a HybridSequential layer, which is a convenience class to build a linear stack of layers, often called a feed-forward neural net.

The “Hybrid” part of name HybridSequential refers to the fact that such a layer can be used with both the Gluon API and the Symbol API.

Using hybrid blocks over dynamic-only blocks (e.g. Sequential) has several advantages apart from being compatible with a wider range of existing code: for instance, the computation graph of the network can be visualized with mxnet.viz.plot_network() and inspected for errors.

Unless a network requires non-static runtime elements like loops, conditionals or random layer selection in its forward pass, it is generally a good idea to err on the side of hybrid blocks.

For details on the differences, see the documentation on Block and HybridBlock.

net = nn.HybridSequential(prefix='MLP_')

with net.name_scope():

net.add(

nn.Flatten(),

nn.Dense(128, activation='relu'),

nn.Dense(64, activation='relu'),

nn.Dense(10, activation=None) # loss function includes softmax already, see below

)

Note: using the name_scope() context manager is optional.

It is, however, good practice since it uses a common prefix for the names of all layers generated in that scope, which can be very helpful during debugging.

Initializing parameters and optimizer¶

Before the network can be used, its parameters (weights and biases) need to be set to initial values that are sufficiently random while keeping the magnitude of gradients limited. The Xavier initializer is usually a good default choice.

Since the net.initialize() method creates arrays for its parameters, it needs to know where to store the values: in CPU or GPU memory.

Like many other functions and classes that deal with memory management in one way or another, the initialize() method takes an optional ctx (short for context) argument, where the return value of either mx.cpu() or mx.gpu() can be provided.

ctx = mx.gpu(0) if mx.context.num_gpus() > 0 else mx.cpu(0)

net.initialize(mx.init.Xavier(), ctx=ctx)

To train the network parameters, we will make use of the stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimizer. More specifically, we use mini-batch SGD in contrast to the classical SGD that processes one example at a time, which is very slow in practice. (Recall that we set the batch size to 100 in the “Loading Data” part.)

Besides the batch size, the SGD algorithm has one important hyperparameter: the learning rate. It determines the size of steps that the algorithm takes in search of parameters that allow the network to optimally fit the training data. Therefore, this value has great influence on both the course of the training process and its final outcome. In general, hyperparameters refer to non-learnable values that need to be chosen before training and that have a potential effect on the outcome. In this example, further hyperparameters are the number of layers in the network, the number of neurons of the first two layers, the activation function and (later) the loss function.

The SGD optimization method can be accessed in MXNet Gluon through the Trainer class.

Internally, it makes use of the SGD optimizer class.

trainer = gluon.Trainer(

params=net.collect_params(),

optimizer='sgd',

optimizer_params={'learning_rate': 0.04},

)

Training¶

Training the network requires a way to tell how well the network currently fits the training data. Following common practice in optimization, this quality of fit is expressed through a loss value (also referred to as badness-of-fit or data discrepancy), which the algorithm then tries to minimize by adjusting the weights of the model.

Ideally, in a classification task, we would like to use the prediction inaccuracy, i.e., the fraction of incorrectly classified samples, to guide the training to a lower value. Unfortunately, inaccuracy is a poor choice for training since it contains almost no information that can be used to update the network parameters (its gradient is zero almost everywhere). As a better behaved proxy for inaccuracy, the softmax cross-entropy loss is a popular choice. It has the essential property of being minimal for the correct prediction, but at the same time, it is everywhere differentiable with nonzero gradient. The accuracy metric is still useful for monitoring the training progress, since it is more intuitively interpretable than a loss value.

Note: SoftmaxCrossEntropyLoss combines the softmax activation and the cross entropy loss function in one layer, therefore the last layer in our network has no activation function.

metric = mx.metric.Accuracy()

loss_function = gluon.loss.SoftmaxCrossEntropyLoss()

Typically, the training is run until convergence, which means that further iterations will no longer lead to improvements of the loss function, and that the network has probably learned a good set of model parameters from the train data. For the purpose of this tutorial, we only loop 10 times over the entire dataset. One such pass over the data is usually called an epoch.

The following steps are taken in each epoch:

- Get a minibatch of

inputsandlabelsfrom thetrain_loader. - Feed the

inputsto the network, producingoutputs. - Compute the minibatch

lossvalue by comparingoutputstolabels. - Use backpropagation to compute the gradients of the loss with respect to each of the network parameters by calling

loss.backward(). - Update the parameters of the network according to the optimizer rule with

trainer.step(batch_size=inputs.shape[0]). - Print the current accuracy over the training data, i.e., the fraction of correctly classified training examples.

num_epochs = 10

for epoch in range(num_epochs):

for inputs, labels in train_loader:

# Possibly copy inputs and labels to the GPU

inputs = inputs.as_in_context(ctx)

labels = labels.as_in_context(ctx)

# The forward pass and the loss computation need to be wrapped

# in a `record()` scope to make sure the computational graph is

# recorded in order to automatically compute the gradients

# during the backward pass.

with autograd.record():

outputs = net(inputs)

loss = loss_function(outputs, labels)

# Compute gradients by backpropagation and update the evaluation

# metric

loss.backward()

metric.update(labels, outputs)

# Update the parameters by stepping the trainer; the batch size

# is required to normalize the gradients by `1 / batch_size`.

trainer.step(batch_size=inputs.shape[0])

# Print the evaluation metric and reset it for the next epoch

name, acc = metric.get()

print('After epoch {}: {} = {}'.format(epoch + 1, name, acc))

metric.reset()

Validation¶

When the above training has completed, we can evaluate the trained model by comparing predictions from the validation dataset with their respective correct labels. It is important to notice that the validation data was not used during training, i.e., the network has not seen the images and their true labels yet. Keeping a part of the data aside for validation is crucial for detecting overfitting of a network: If a neural network has enough parameters, it can simply memorize the training data and look up the true label for a given training image. While this results in 100 % training accuracy, such an overfit model would perform very poorly on new data. In other words, an overfit model does not generalize to a broader class of inputs than the training set, and such an outcome is almost always undesirable. Therefore, having a subset of “unseen” data for validation is an important part of good practice in machine learning.

To validate our model on the validation data, we can run the following snippet of code:

metric = mx.metric.Accuracy()

for inputs, labels in val_loader:

# Possibly copy inputs and labels to the GPU

inputs = inputs.as_in_context(ctx)

labels = labels.as_in_context(ctx)

metric.update(labels, net(inputs))

print('Validaton: {} = {}'.format(*metric.get()))

assert metric.get()[1] > 0.96

If everything went well, we should see an accuracy value that is around 0.968, which means that we are able to accurately predict the digit in 97 % of test images. This is a pretty good result, but as we will see in the next part of this tutorial, we can do a lot better than that.

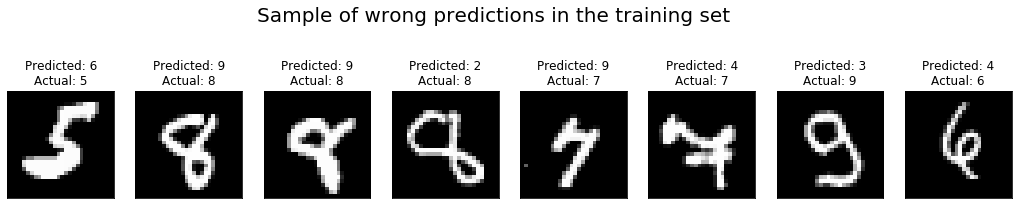

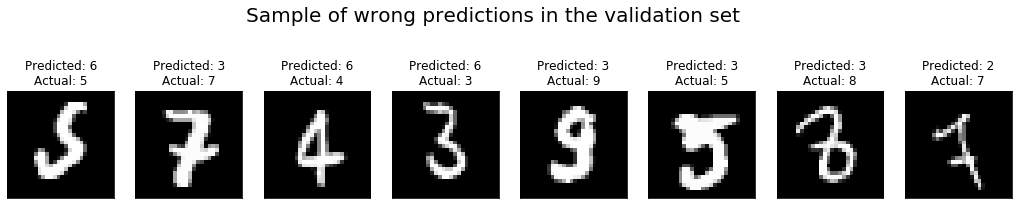

That said, a single number only conveys very limited information on the performance of our neural network. It is always a good idea to actually look at the images on which the network performed poorly, and check for clues on how to improve the performance. We do that with the help of a small function that produces a list of the images which the network got wrong, together with the predicted and true labels.

def get_mislabeled(loader):

"""Return list of ``(input, pred_lbl, true_lbl)`` for mislabeled samples."""

mislabeled = []

for inputs, labels in loader:

inputs = inputs.as_in_context(ctx)

labels = labels.as_in_context(ctx)

outputs = net(inputs)

# Predicted label is the index is where the output is maximal

preds = nd.argmax(outputs, axis=1)

for i, p, l in zip(inputs, preds, labels):

p, l = int(p.asscalar()), int(l.asscalar())

if p != l:

mislabeled.append((i.asnumpy(), p, l))

return mislabeled

We can now get the mislabeled images in the training and validation sets and plot a selection of them:

import numpy as np

sample_size = 8

wrong_train = get_mislabeled(train_loader)

wrong_val = get_mislabeled(val_loader)

wrong_train_sample = [wrong_train[i] for i in np.random.randint(0, len(wrong_train), size=sample_size)]

wrong_val_sample = [wrong_val[i] for i in np.random.randint(0, len(wrong_val), size=sample_size)]

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

fig, axs = plt.subplots(ncols=sample_size)

for ax, (img, pred, lbl) in zip(axs, wrong_train_sample):

fig.set_size_inches(18, 4)

fig.suptitle("Sample of wrong predictions in the training set", fontsize=20)

ax.imshow(img[0], cmap="gray")

ax.set_title("Predicted: {}\nActual: {}".format(pred, lbl))

ax.xaxis.set_visible(False)

ax.yaxis.set_visible(False)

fig, axs = plt.subplots(ncols=sample_size)

for ax, (img, pred, lbl) in zip(axs, wrong_val_sample):

fig.set_size_inches(18, 4)

fig.suptitle("Sample of wrong predictions in the validation set", fontsize=20)

ax.imshow(img[0], cmap="gray")

ax.set_title("Predicted: {}\nActual: {}".format(pred, lbl))

ax.xaxis.set_visible(False)

ax.yaxis.set_visible(False)

In this case, it is rather obvious that our MLP network is either too simple or has not been trained long enough to perform really great on this dataset, as can be seen from the fact that some of the mislabeled examples are rather “easy” and should not be a challenge for our neural net. As it turns out, moving to the CNN architecture presented in the following section will give a big performance boost.

Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)¶

A fundamental issue with the MLP network is that it requires the inputs to be flattened (in the non-batch axes) before they can be processed by the dense layers. This means in particular that the spatial structure of an image is largely discarded, and that the values describing it are just treated as a long vector. The network then has to figure out the neighborhood relations of pixels from scratch by adjusting its weights accordingly, which seems very wasteful.

A CNN aims to address this problem by using a more structured weight representation. Instead of connecting all inputs to all outputs, the characteristic convolution layer only considers a small neighborhood of a pixel to compute the value of the corresponding output pixel. In particular, the spatial structure of the image is preserved, i.e., one can speak of input and output pixels in the first place. Only the size of the image may change through convolutions. This article gives a good and intuitive explanation of convolutions in the context of deep learning.

The size of the neighborhood that a convolution layer considers for each pixel is usually referred to as filter size or kernel size. The array of weights – which does not depend on the output pixel location, only on the position within such a neighborhood – is called filter or kernel. Typical filter sizes range from 3 x 3 to 13 x 13, which implies that a convolution layer has far fewer parameters than a dense layer.

conv_layer = nn.Conv2D(kernel_size=(3, 3), channels=32, in_channels=16, activation='relu')

print(conv_layer.params)

Parameter conv0_weight (shape=(32, 16, 3, 3), dtype=

Parameter conv0_bias (shape=(32,), dtype=

Filters can be thought of as little feature detectors: in early layers, they learn to detect small local structures like edges, whereas later layers become sensitive to more and more global structures.

Since images often contain a rich set of such features, it is customary to have each convolution layer employ and learn many different filters in parallel, so as to detect many different image features on their respective scales.

This stacking of filters, which directly translates to a stacking of output images, is referred to as output channels of the convolution layer.

Likewise, the input can already have multiple channels.

In the above example, the convolution layer takes an input image with 16 channels and maps it to an image with 32 channels by convolving each of the input channels with a different set of 32 filters and then summing over the 16 input channels.

Therefore, the total number of filter parameters in the convolution layer is channels * in_channels * prod(kernel_size), which amounts to 4608 in the above example.

Another characteristic feature of CNNs is the usage of pooling, i.e., summarizing patches to a single number, to shrink the size of an image as it travels through the layers. This step lowers the computational burden of training the network, but the main motivation for pooling is the assumption that it makes the network less sensitive to small translations, rotations or deformations of the image. Popular pooling strategies are max-pooling and average-pooling, and they are usually performed after convolution.

The following code defines a CNN architecture called LeNet.

The LeNet architecture is a popular network known to work well on digit classification tasks.

We will use a version that differs slightly from the original in the usage of tanh activations instead of sigmoid.

lenet = nn.HybridSequential(prefix='LeNet_')

with lenet.name_scope():

lenet.add(

nn.Conv2D(channels=20, kernel_size=(5, 5), activation='tanh'),

nn.MaxPool2D(pool_size=(2, 2), strides=(2, 2)),

nn.Conv2D(channels=50, kernel_size=(5, 5), activation='tanh'),

nn.MaxPool2D(pool_size=(2, 2), strides=(2, 2)),

nn.Flatten(),

nn.Dense(500, activation='tanh'),

nn.Dense(10, activation=None),

)

To get an overview of all intermediate sizes of arrays and the number of parameters in each layer, the summary() method can be a great help.

It requires the network parameters to be initialized, and an input array to infer the sizes.

lenet.initialize(mx.init.Xavier(), ctx=ctx)

lenet.summary(nd.zeros((1, 1, 28, 28), ctx=ctx))

Output:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Layer (type) Output Shape Param #

================================================================================

Input (1, 1, 28, 28) 0

Activation-1 <Symbol eNet_conv0_tanh_fwd> 0

Activation-2 (1, 20, 24, 24) 0

Conv2D-3 (1, 20, 24, 24) 520

MaxPool2D-4 (1, 20, 12, 12) 0

Activation-5 <Symbol eNet_conv1_tanh_fwd> 0

Activation-6 (1, 50, 8, 8) 0

Conv2D-7 (1, 50, 8, 8) 25050

MaxPool2D-8 (1, 50, 4, 4) 0

Flatten-9 (1, 800) 0

Activation-10 <Symbol eNet_dense0_tanh_fwd> 0

Activation-11 (1, 500) 0

Dense-12 (1, 500) 400500

Dense-13 (1, 10) 5010

================================================================================

Parameters in forward computation graph, duplicate included

Total params: 431080

Trainable params: 431080

Non-trainable params: 0

Shared params in forward computation graph: 0

Unique parameters in model: 431080

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

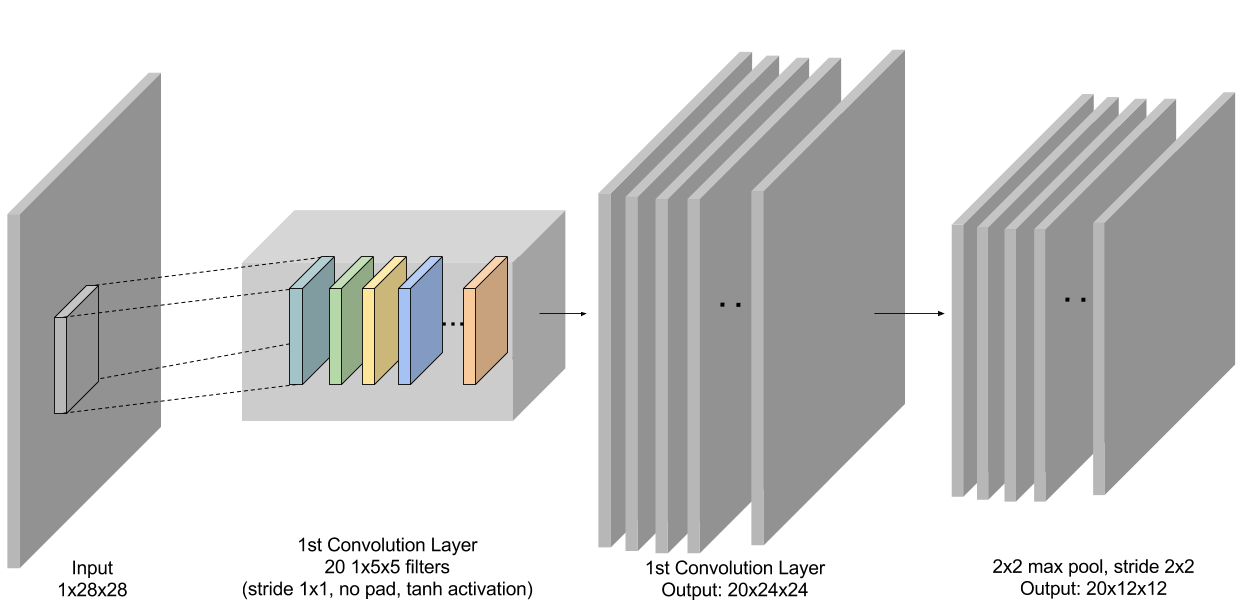

Figure 3: First conv + pooling layer in LeNet.

Now we train LeNet with similar hyperparameters and procedure as before. Note that it is advisable to use a GPU if possible, since this model is significantly more computationally demanding to evaluate and train than the previous MLP.

trainer = gluon.Trainer(

params=lenet.collect_params(),

optimizer='sgd',

optimizer_params={'learning_rate': 0.04},

)

metric = mx.metric.Accuracy()

num_epochs = 10

for epoch in range(num_epochs):

for inputs, labels in train_loader:

inputs = inputs.as_in_context(ctx)

labels = labels.as_in_context(ctx)

with autograd.record():

outputs = lenet(inputs)

loss = loss_function(outputs, labels)

loss.backward()

metric.update(labels, outputs)

trainer.step(batch_size=inputs.shape[0])

name, acc = metric.get()

print('After epoch {}: {} = {}'.format(epoch + 1, name, acc))

metric.reset()

for inputs, labels in val_loader:

inputs = inputs.as_in_context(ctx)

labels = labels.as_in_context(ctx)

metric.update(labels, lenet(inputs))

print('Validaton: {} = {}'.format(*metric.get()))

assert metric.get()[1] > 0.985

If all went well, we should see a higher accuracy metric for predictions made using LeNet. With this CNN we should be able to correctly predict around 99% of all validation images.

Summary¶

In this tutorial, we demonstrated how to use MXNet to solve a standard computer vision problem: classifying images of hand-written digits. We showed how to quickly build, train and evaluate models such as MLPs and CNNs with the MXNet Gluon package.