Automatic Differentiation¶

Why do we need to calculate gradients?¶

Short Answer:¶

Gradients are fundamental to the process of training neural networks, and tell us how to change the parameters of the network to improve its performance.

Long Answer:¶

Under the hood, neural networks are composed of operators (e.g. sums, products, convolutions, etc) some of which use parameters (e.g. the weights in convolution kernels) for their computation, and it’s our job to find the optimal values for these parameters. Gradients lead us to the solution!

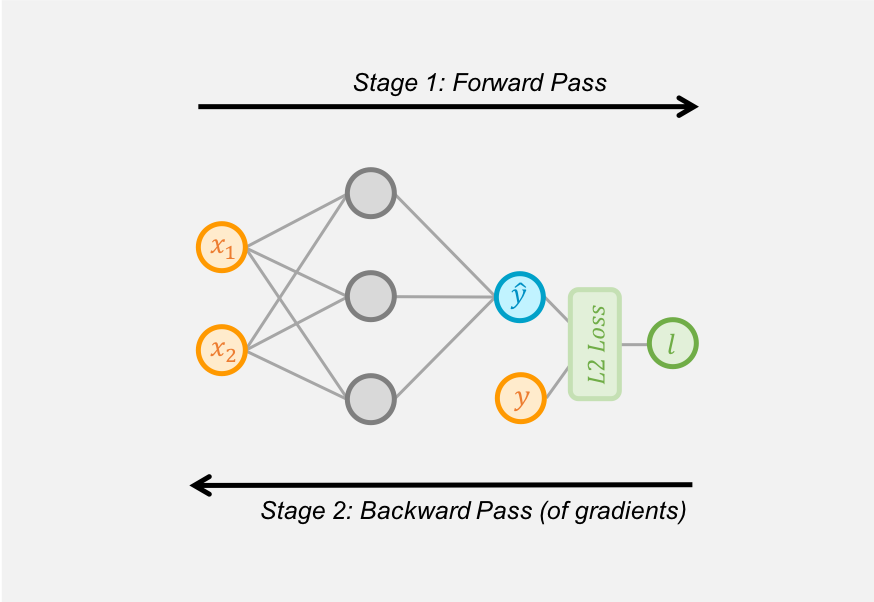

Gradients tell us how much a given variable increases or decreases when we change a variable it depends on. What we’re interested in is the effect of changing a each parameter on the performance of the network. We usually define performance using a loss metric that we try to minimize, i.e. a metric that tells us how bad the predictions of a network are given ground truth. As an example, for regression we might try to minimize the L2 loss (also known as the Euclidean distance) between our predictions and true values, and for classification we minimize the cross entropy loss.

Assuming we’ve calculated the gradient of each parameter with respect to the loss (details in next section), we can then use an optimizer such as stochastic gradient descent to shift the parameters slightly in the opposite direction of the gradient. See Optimizers for more information on these methods. We repeat the process of calculating gradients and updating parameters over and over again, until the parameters of the network start to stabilize and converge to a good solution.

How do we calculate gradients?¶

Short Answer:¶

We differentiate. MXNet Gluon uses Reverse Mode Automatic Differentiation (autograd) to backprogate gradients from the loss metric to the network parameters.

Long Answer:¶

One option would be to get out our calculus books and work out the gradients by hand. Who wants to do this though? It’s time consuming and error prone for starters. Another option is symbolic differentiation, which calculates the formulas for each gradient, but this quickly leads to incredibly long formulas as networks get deeper and operators get more complex. We could use finite differencing, and try slight differences on each parameter and see how the loss metric responds, but this is computationally expensive and can have poor numerical precision.

What’s the solution? Use automatic differentiation to backpropagate the gradients from the loss metric back to each of the parameters. With backpropagation, a dynamic programming approach is taken to efficently calculate gradients. Sometimes this is called reverse mode automatic differentiation, and it’s very efficient in ‘fan-in’ situations where many parameters effect a single loss metric. Although forward mode automatic differentiation methods exist, they’re suited to ‘fan-out’ situations where few parameters effect many metrics, which isn’t the case for training neural networks.

How does Automatic Differentiation (autograd) work?¶

Short Answer:¶

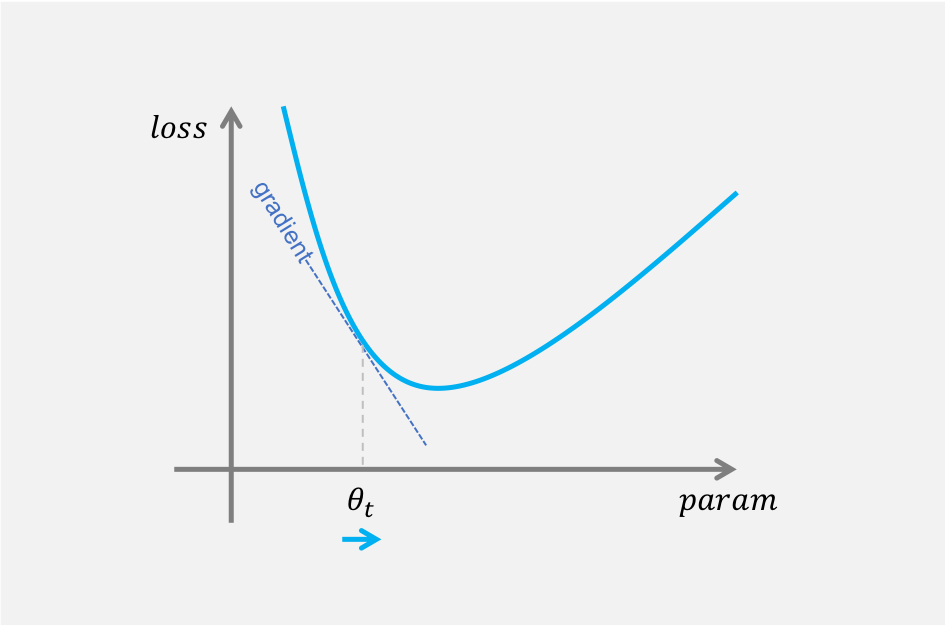

Stage 1. Create a record of the operators used by the network to make predictions and calculate the loss metric. Called the ‘forward pass’ of training. Stage 2. Work backwards through this record and evaluate the partial derivatives of each operator, all the way back to the network parameters. Called the ‘backward pass’ of training.

Long Answer:¶

All operators in MXNet have two methods defined: a forward method for executing the operator as expected, and a backward method that returns the partial derivative (the derivative of the output with respect to the input). On the vary rare occasion you need to implement your own custom operator, you’ll define the same two methods.

Automatic differentiation creates a record of the operators used (i.e. the forward method calls) by the network to make predictions and calculate the loss metric. A graph structure is used to record this, capturing the inputs (including their value) and outputs for each operator and how the operators are related. We call this the ‘forward pass’ of training.

Automatic differentiation then works backwards through each operator of the graph, calling the backward method on each operator to calculate the partial derivative and calculate the gradient of the loss metric with respect to the operator’s input (which could be parameters). Usually we work backwards from the loss metric, and hence calculate the gradients of the loss metric, but this can be done from any output. We call this the ‘backward pass’ of training.

What are the advantages of Automatic Differentiation (autograd)?¶

Short Answer:¶

It’s flexible, automatic and efficient. You can use native Python control flow operators such as if conditions and while loops and autograd will still be able to backpropogate the gradients correctly.

Long Answer:¶

A huge benefit of using autograd is the flexibility it gives you when defining your network. You can change the operations on every iteration, and autograd will still be able to backpropogate the gradients correctly. You’ll sometimes hear these called ‘dynamic graphs’, and are much more complex to implement in frameworks that require static graphs, such as TensorFlow.

As suggested by the name, autograd is automatic and so the complexities of the backpropogation procedure are taken care of for you. All you have to do is tell autograd when you’re interested in recording gradients, and specify what gradients you’re interested in calculating: this will nearly always just be the gradient of the loss metric. And these gradient calculations will be performed efficiently too.

How do I use autograd in MXNet Gluon?¶

Step one is to import the autograd package.

[1]:

from mxnet import autograd

As a simple example, we’ll implement the regression model shown in the diagrams above, and later use autograd to automatically calculate the gradient of the loss with respect to each of the weight parameters.

[2]:

import mxnet as mx

from mxnet.gluon.nn import HybridSequential, Dense

from mxnet.gluon.loss import L2Loss

# Define network

net = HybridSequential()

net.add(Dense(units=3))

net.add(Dense(units=1))

net.initialize()

# Define loss

loss_fn = L2Loss()

# Create dummy data

x = mx.np.array([[0.3, 0.5]])

y = mx.np.array([[1.5]])

[04:45:39] /work/mxnet/src/storage/storage.cc:202: Using Pooled (Naive) StorageManager for CPU

We’re ready for our first forward pass through the network, and we want autograd to record the computational graph so we can calculate gradients. One of the simplest ways to do this is by running the network (and loss) code in the scope of an autograd.record context.

[3]:

with autograd.record():

y_hat = net(x)

loss = loss_fn(y_hat, y)

Only operations that we want recorded are in the scope of the autograd.record context (since there is a computational overhead), and autograd should now have constructed a graph of these operations ready for the backward pass. We start the backward pass by calling the backward method on the quantity of interest, which in this case is loss since were trying to calculate the gradient of the loss with respect to the parameters.

Remember: if loss isn’t a single scalar value (e.g. could be a loss for each sample, rather than for whole batch) a sum operation will be applied implicitly before starting the backward propagation, and the gradients calculated will be of this sum with respect to the parameters.

[4]:

loss.backward()

And that’s it! All the autograd magic is complete. We should now have gradients for each parameter of the network, which will be used by the optimizer to update the parameter values for improved performance. Check out the gradients of the first layer for example:

[5]:

net[0].weight.grad()

[5]:

array([[-0.01425944, -0.02376572],

[ 0.00991847, 0.01653079],

[ 0.02987554, 0.04979257]])

Advanced: Switching between training vs inference modes¶

Some neural network layers behave differently depending on whether you’re training the network or running it for inference. One example is Dropout, where activations are set to 0 at random during training, but remain unchanged during inference. Another is BatchNorm, where local batch statistics are used to normalize while training, but global statistics are used during inference.

With MXNet Gluon, autograd is critical for switching between training and inference modes. As the default, networks will run in inference mode. While autograd is recording though, networks will run in training mode. Operations under the autograd.record() context scope are an example of this.

Creating a network of a single Dropout block will demonstrate this.

[6]:

dropout = mx.gluon.nn.Dropout(rate=0.5)

data = mx.np.ones(shape=(3,3))

output = dropout(data)

is_training = autograd.is_training()

print('is_training:', is_training, output)

is_training: False [[1. 1. 1.]

[1. 1. 1.]

[1. 1. 1.]]

We called dropout when autograd wasn’t recording, so our network was in inference mode and thus we didn’t see any dropout of the input (i.e. it’s still ones). We can confirm the current mode by calling autograd.is_training().

[7]:

with autograd.record():

output = dropout(data)

print('is_training:', is_training, output)

is_training: False [[0. 2. 0.]

[0. 0. 2.]

[0. 2. 2.]]

We called dropout while autograd was recording this time, so our network was in training mode and we see dropout of the input this time. Since the probability of dropout was 50%, the output is automatically scaled by 1/0.5=2 to preserve the average activation.

We can force some operators to behave as they would during training, even in inference mode. One example is setting mode='always' on the Dropout operator, but this usage is uncommon.

Advanced: Skipping the calculation of parameter gradients¶

When creating neural networks with MXNet Gluon it is assumed that you’re interested in the gradients of the loss with respect to each of the network’s parameters. We’re usually training the whole network, so this is exactly what we want. When we call net.initialize(), the network parameters get (lazily) initalized and memory is also allocated for the gradients, esentially doubling the space required for each parameter. After performing a forward and backward pass through the network, we will

have gradients for all of the parameters.

Sometimes we don’t need the gradients for all of the parameters though. One example would be ‘freezing’ the values of the parameters in certain layers. Since we don’t need to update the values, we don’t need the gradients. Using the grad_req property of a parameter and setting it to 'null', we can indicate this to autograd, saving us computation time and memory.

[8]:

net[0].weight.grad_req = 'null'

Advanced: Calculating non-parameter gradients¶

Although it’s most common to deal with network parameters (with Parameter being an MXNet Gluon abstraction), there are cases when you need to calculate the gradient with respect to thing that are not parameters (i.e. standard ndarrays). One example would be finding the gradient of the loss with respect to the input data to generate adversarial examples.

With autograd it’s simple, but there’s one key difference compared to parameters: parameters are assumed to require gradients by default, non-parameters are not. We need to explicitly state that we require the gradient, and we do that by calling .attach_grad() on the ndarray. We can then access the gradient using .grad after the backward pass.

As a simple example, let’s take the case where \(y=2x^2\) and use autograd to calculate gradient of \(y\) with respect to \(x\) at three different values of \(x\). We could obviously work out the gradient by hand in this case as \(dy/dx=4x\), but let’s use this knowledge to check autograd. Given \(x\) is an ndarray and not a Parameter, we need to call x.attach_grad().

[9]:

x = mx.np.array([1, 2, 3])

x.attach_grad()

with autograd.record():

y = 2 * x ** 2

y.backward()

print(x.grad)

[ 4. 8. 12.]

Advanced: Using Python control flow¶

As mentioned before, one of the main advantages of autograd is the ability to automatically calculate gradients of dynamic graphs (i.e. graphs where the operators could be different on every forward pass). One example of this would be applying a tree structured recurrent network to parse a sentence using its parse tree. And we can use Python control flow operators to create a dynamic flow that depends on the data, rather than using MXNet’s control flow operators.

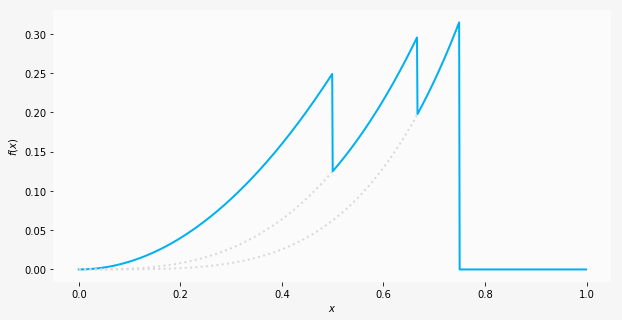

We’ll write a function as a toy example of a dynamic network. We’ll add an if condition and a loop with a variable number of iterations, both of which will depend on the input data. Although these can now be used in static graphs (with conditional operators) it’s still much more natural to use native control flow.

[10]:

import math

def f(x):

y = x # going to change y but still want to use x

if x < 0.75: # variable num_loops because it depends on x

num_loops = math.floor(1/(1-x.item()))

for i in range(num_loops):

y = y * x # increase polynomial degree

else: # otherwise flatline

y = y * 0

return y

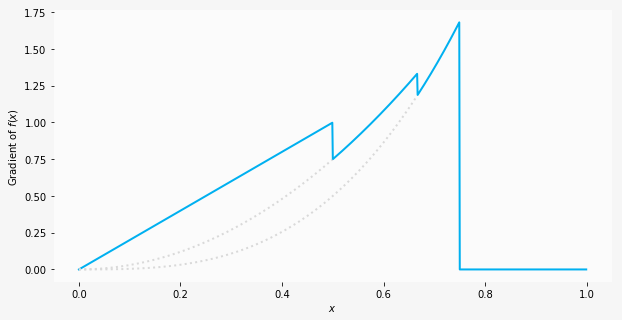

We can plot the resultant function for \(x\) between 0 and 1, and we should recognise certain functions in segments of \(x\). Starting with a quadratic curve from 0 to 1/2, we have a cubic curve from 1/2 to 2/3, a quartic from 2/3 to 3/4 and finally a flatline.

Using autograd, let’s now find the gradient of this arbritrary function. We don’t have a vectorized function in this case, because of the control flow, so let’s also create a function to calculate the gradient using autograd.

[11]:

def get_grad(f, x):

x.attach_grad()

with autograd.record():

y = f(x)

y.backward()

return x.grad

xs = mx.np.arange(0.0, 1.0, step=0.1)

grads = [get_grad(f, x).item() for x in xs]

print(grads)

[0.0, 0.20000000298023224, 0.4000000059604645, 0.6000000238418579, 0.800000011920929, 0.75, 1.0800000429153442, 1.371999979019165, 0.0, 0.0]

We can calculate the gradients by hand in this situation (since it’s a toy example), and for the four segments discussed before we’d expect \(2x\), \(3x^2\), \(4x^3\) and 0. As a spot check, for \(x=0.6\) the hand calculated gradient would be \(3x^2=1.08\), which equals 1.08 as computed by autograd.

Advanced: Custom head gradients¶

Most of the time autograd will be aware of the complete computational graph, and be able to calculate the gradients automatically. On a few rare occasions, you might have external post processing components (outside of MXNet Gluon) but still want to compute gradients with respect to MXNet Gluon network parameters.

autograd enables this functionality by letting you pass in custom head gradients to .backward(). When nothing is specified (for the majority of cases), autograd will just used ones by default. Say we’re interested in calculating \(dz/dx\) but only calculate an intermediate variable \(y\) using MXNet Gluon. We need to first calculate the head gradient \(dz/dy\) (manually or otherwise), and then pass this to .backward(). autograd will then use this to calculate

\(dz/dx\), applying the chain rule.

As an example, let’s take \(y=x^3\) (calculated with mxnet) and \(z=y^2\). (calculated with numpy). We can manually calculate \(dz/dy=2y\) (once again with numpy), and use this as the head gradient for autograd to automatically calculate \(dz/dx\). Applying the chain rule by hand we could calculate \(dz/dx=6x^5\), so for \(x=2\) we expect \(dz/dx=192\). Let’s check to see whether autograd calculates the same.

[12]:

x = mx.np.array([2,])

x.attach_grad()

# compute y inside of mxnet (with `autograd`)

with autograd.record():

y = x**3

# compute dz/dy outside of mxnet

y_np = y.asnumpy()

z_np = y_np**2

dzdy_np = 2*y_np

# compute dz/dx inside of mxnet (given dz/dy)

dzdy = mx.np.array(dzdy_np)

y.backward(dzdy)

print(x.grad)

[192.]

And as expected, we get a gradient of 192 for x.